Globally, eCommerce is facing two parallel trends. On one hand, Amazon has cemented itself as a dominant force in the market and seemingly continues to go from strength to strength, dominating by bundling all functions and services of commerce and delivering it to consumers at an unmatched standard and speed. On the other hand, now more than ever, we are seeing the rise of microbrands intent on shaking up the market.

Microbrands operate a direct-to-consumer (DTC) model and are shaped by a combination of customer centricity, ease and convenience. By stripping out the middleman, they are building a relationship directly with their consumers, allowing them to foster highly engaged communities that deeply care about the products they develop. Not only this, but the direct-to-consumer model allows for access to data that they can use to inform their strategies, e.g. in areas like pricing, design and market expansion.

With technology as their native language, microbrands are bred online and designed to move fast. They are mobile-first, hyper-social, channel fluid and deliver a seamless buying experience to internet-savvy consumers with extremely high expectations. These differences point to a significant gap between what consumers want and what traditional retail offers. The shift in customer expectations is a danger to brands in every vertical, but its Consumer Packaged Goods (CPG) brands that face the greatest threat so far.

Large manufacturers rely on big retailers – like Walmart and CVS in the US and Argos in the UK – to get their products into the hands of the customer. Unfortunately, manufacturers have little control over the retail environment and cannot fully control the brand experience at the point of sale. For most shoppers nowadays, this is no longer enough – they want a personalised and memorable interaction with the brand and the product. When customers are buying through a wholesale model, it makes customisation and a single customer view almost impossible for most CPG brands.

The bottom line is consumers are more empowered and demanding than ever, and if CPG brands do not react to this by changing their relationship with them to reflect that, their business will struggle to keep up. However, CPG brands who can get ahead of these expectations will have an unprecedented advantage. Established CPG brands touch on a wider audience than any other vertical, meaning the data they have on their consumer behaviour is unparalleled. If they can harness that data, take direction from challengers and bridge the gap between digital and physical experiences, established players will be able to flourish in an increasingly disruptive market.

As for the microbrands that are increasingly dominating the space, the retail landscape continues to evolve in such a way that will further propel their position in the market. A recent YouGov survey substantiated this by concluding that 40% of US consumers expect more than 40% of their spending in the next five years will go toward direct-to-consumer brands such as Away, The Honest Company and Casper.

How are microbrands driving change?

One reason for the rise of microbrands is that that new wave backend solutions such as Shopify and Magento mean that microbrands have a lower barrier to entry into the market.

Shopify provides online domains from as little as $29 a month and handles the back-end infrastructure that would have formerly cost hundreds of thousands of dollars to build. However, whilst it is certainly easier now to enter the online space, the challenge these brands face is how to remain competitive if the barriers to entry are lowered and the emergence of microbrands flood the market. Microbrands must now stand out not only against the category leaders, but also against several other challengers who have recognised the potential to disrupt.

According to analysis from IRI-BCG, in 2017 microbrands within the CPG industry continued to take market share from their midsize and large rivals. Whilst the revenues of large CPG companies remained roughly flat, with only 0.2% year-on-year growth, small companies grew by approximately 2.3%. In absolute terms, the growth is significant. Between 2012 and 2017, small players grabbed approximately $15 billion in sales from their larger counterparts.

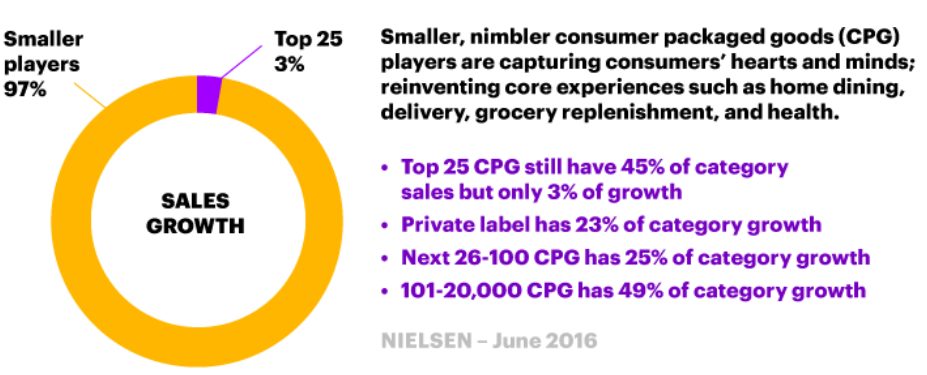

The chart below puts into perspective the proliferation of microbrands within the consumer goods industry. Whilst the top 25 companies still have 45% of category value, they are registering growth of only 3%. By contrast, microbrands represent 97% of category growth globally.

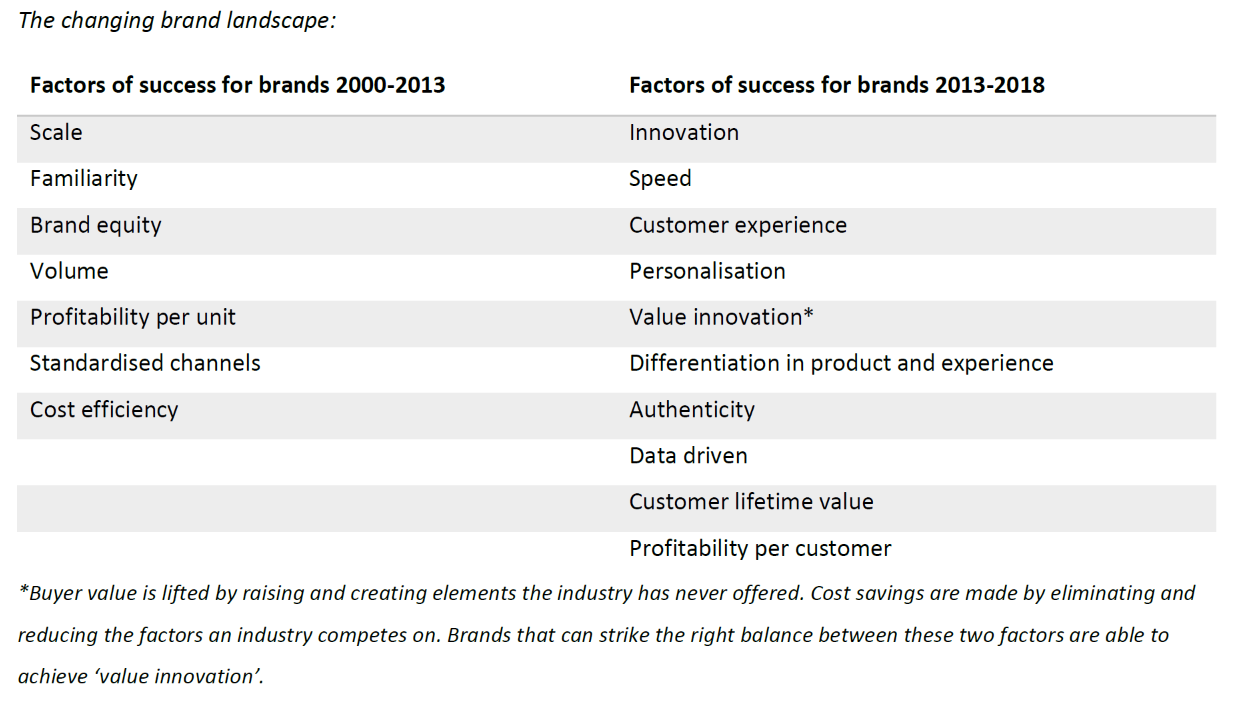

Critically, the fact is not that being small is a competitive advantage, but rather that scale no longer serves as the primary basis of competition. The most successful microbrands are distinguishing themselves in several ways that allow them to innovate, incubate, and scale with speed, precision and predictability.

Microbrands need to navigate a significant rise in complexity in all aspects of their business. Personalisation requires real-time insights and more digital interaction with consumers, customised products will require new manufacturing capabilities, and localisation will require a diversification of the product offering.

To manage the added complexities, they must become data-driven organisations. They need to gather insights across all functions to identify new opportunities, to break conventions that produce generic customer experiences and to create a portfolio of differentiated offerings with an authentic feel. They need to unify everything from demand generation, to purchase, to servicing, and they need to do so in a cost-effective way that unlocks capital for continuous innovation.

Generally, price is no longer a detractor to purchase, provided that the expectations of the customer are met on all other accounts. As such, microbrands who innovate and offer something different can expect to achieve higher margins by selling their products for a premium price that is commensurate with the value of the innovations they make to their products. Not only must microbrands innovate and drive value in their product offering, but their customer experience must also deliver on this. According to Gartner, 89% of companies now compete primarily on the basis of customer experience. Therefore, if your experience is more meaningful and impactful than your competitors’, it will win over customers irrespective of price. A PwC study found that buyers will pay up to 16% more for a better experience.

Leading microbrands

Casper

Mattress company Casper is a good example of a brand that has delivered on value innovation. It has successfully pioneered the mattress-in-a-box concept with an innovative foam design that easily compresses into a box and can be shipped to your door at price points well below $1,000.

LOLA

Feminine hygiene brand LOLA provides a good example of a brand that delivers on customer experience. Offering a subscription service, it allows its customers to pick and choose a selection of products online that meet their needs, instead of purchasing a pre-selected assortment of products in store. Crucially, this process of self-selection helps the brand understand their customers’ needs, suggest new products and develop and test and new offerings in a way that encourages loyalty and builds on lifetime value.

Glossier

Beauty brand Glossier avoids the mass feel of big brands and delivers on differentiation, leveraging customer communities as a platform for organic distribution for the brand. The brand originated from a blog and then backsolved eCommerce, having aggregated an avid audience and learned what they wanted from a product, brand and distribution perspective. Glossier fuels its online community through brand advocacy on social media platforms, e.g. Facebook and Instagram. The authenticity of the brand comes from the fact that its consumers act as ambassadors for the brand. The vision of CEO Emily Weiss is that, ultimately, “the brands of the future are going to be co-created”.

How are legacy CPG brands responding to disruption from microbrands?

Consumer goods giants are aware of the threat posed by microbrands and one reaction is to acquire them. Unilever bought Dollar Shave Club, a subscription service for men’s grooming products, for $1 billion in 2016, grabbing the market share the start-up had itself taken from Gillette. Unilever is not acting alone, with the biggest 10 consumer goods firms all having recently invested in direct-to-consumer start-ups. Nestlé’s acquisition in 2017 of Blue Bottle, a hip Californian coffee brand, bought it exposure to new market segments.

However, competition is fierce to buy the best microbrands, so big firms may overpay for their acquisition. Marc Pritchard, the Chief Brand Officer of Procter & Gamble, explaining its purchase last year of Native, a small deodorant brand, explicitly referred to its DTC model, saying it is “where things are going”. Other big firms are trying to grow their own brands. Earlier this year, Kraft Heinz launched Springboard, an incubator for small, disruptive food and drink brands. The likelihood is that in the long run, some small brands will be swallowed up, but others will be encouraged – more will want to remain independent for longer, or entirely, which will mean larger deals or IPOs.

What are the key considerations for your brands?

- Understand what drives your growth versus that of your competitors. Leading companies focus on core strengths – whether that be in manufacturing, new product development, customisation, sales and marketing – and outsource the rest, taking advantage of the ongoing deconstruction of the CPG value chain. Establishing your brand’s unique selling point is fundamental in giving the brand a competitive edge and allows the brand to carve out and build a relationship with its target market.

- Where possible, avoid using pricing as a tactic to drive dollar growth. Instead focus on developing innovations and differentiation in your product offering that boosts perceived value of the product. When the perceived value is greater, the consumer is more willing to pay a premium price for that product, and as such, brands who successfully deliver on value should expect to strategically drive up product prices and achieve greater margins.

- Consider capturing small-brand growth opportunities. Top companies regularly evaluate the viability of venture units, incubators and M&A and promote intrapreneurial behaviour within the business.

- Adopt a data-driven approach to understand evolving customer behaviours. Leverage data to expand your understanding of consumer demand – not only what consumers want to buy, but where, how and why they want to buy it, and use those insights to deliver revenue-driving and cost-saving changes.

Summary

It is fair to say that Amazon’s relentless growth is not happening in silos. It is taking place against a backdrop of multiple channels, agile tech platforms, and digitally-savvy young consumers with increasing influence. The ability to harness data, along with fast iteration, is fuelling the rise of microbrands – and companies who fail to adopt the microbrand mentality, or that make sub-optimal choices will be left behind by more thoughtful, action-oriented competitors.

That said, it is not only the traditional players that need to re-think their strategies to remain competitive, the microbrands themselves must work harder than ever before to develop a compelling proposition that places them ahead of the curve, in an increasingly fast-paced and demanding retail environment. The reality is that these niche brands now exist in a sea of so many, and so to break through the noise is increasingly challenging (and expensive).